She comes back to me in reels of dreams to taunt spring last down my throat. Mercilessly. It was a time when hints of the color pink had just reappeared in this gloomy city. I was nearly done with my undergraduate degree, save for some French classes and a dissertation to submit, and so I exercised my free will to wake up just before ten every morning. I’d tackle every tooth with my newly-bought electric toothbrush and do my grand three-step skincare routine, finishing it off with a Medicube Age-R Booster Pro that isn’t mine but that sits on the bathroom shelf. I’d make the most breakfast of breakfasts, then either read or journal. Once my most breakfast of breakfasts has settled, I’d be off to the gym for a two-hour workout because I’d been dismayed by someone on social media saying, “your morning skinny is someone else’s worst nightmare.” I do not have the healthiest relationship with my body. Then again, I do not have the healthiest relationships, period. I’d then spend the remainder of my day staring at a graduate job offer letter I was too creative to accept and too financially unstable to reject. Dinner would always be a twenty-minute pasta job, and my nights would be spent on more reading, writing, gossiping (good for the soul), and swiping (mostly left) on Hinge—despite being the kind of person who writes: To eat out of his hand while still gazing into him, just so that when the crumbs are gone, I get to kneel in his palm. There is no obedience or sacrifice. It’s wanting. Or maybe I don’t want to kneel in his palm exposed to the rest of the world. Maybe I should like to crawl myself into the soft folds of his mouth like a thing that needs taking care of. Not that I need taking care of, necessarily, but he does it so well, and who am I to refuse?

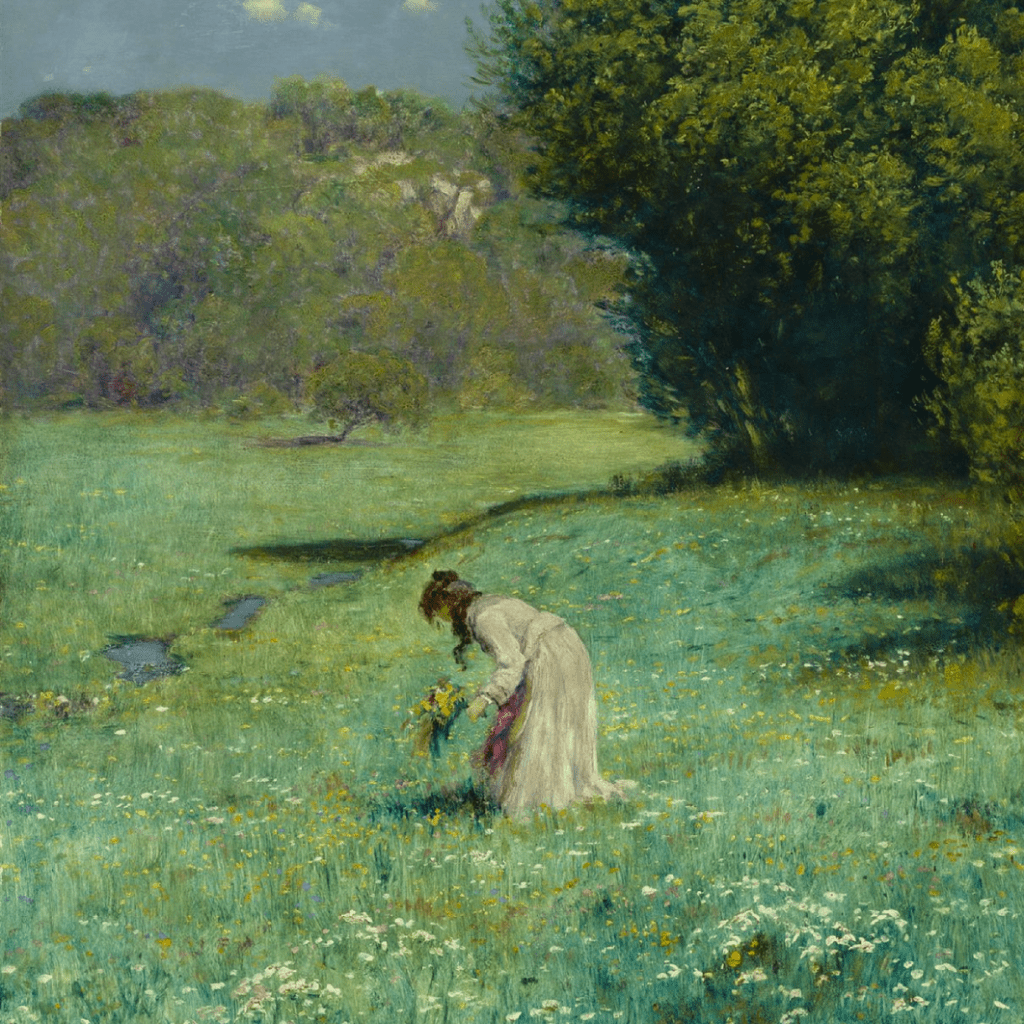

Spring last existed in a different plane, one that is no longer accessible. Still, since the sun is out and the meadow is green again, I lean back against the old sycamore tree and play fetch with the canine in me.

playing fetch

To be a writer is to play an eternal game of fetch. You throw something you think you know out into the open and wait for it to return in a slightly different form. You repeat this process (with utmost enthusiasm, of course—any hint of dread and all progress will be nullified) until the thing that returns no longer resembles the thing that you initially cast out, you mourn, and you move on to the next thing.

Playing fetch sounds easy, repetitive even, but that is rarely the case. To begin with, you first need a good grasp of the initial thing—not who you are playing fetch with (it’s always yourself), but what you are playing fetch with. This inaugural description is almost always factual, objective, and simple. You will never fail to find the right words to call it what it is. Then comes the throwing. Summon all the might in your non-dominant arm as you hold the thing carelessly; there is no need for much care when you expect it to come back. The reason for using your non-dominant arm is that you should not be the sole dictator of how far you cast the thing out. Sometimes, the strength comes not from yourself but from the elements that surround you. And so the force with which you swing dictates the time that needs to pass before the thing comes back to you between the jaws of the canine of your subconscious. In the meantime, you roll around the meadow in a dress shirt you do not mind muddying, put little words to paper, pick a spring bouquet, and accidentally nurse a whole bottle while you ponder how you’ve managed to compartmentalize three and twenty years of life. You hang the laundry and do the dishes, and by the time you come back to the sycamore tree, a canine flings itself your way, but you no longer recall the initial pitch you made. The canine drops the thing from its mouth, and you feel the need to sink onto the soft ground to decipher the thing. But now, the factualness, the objectiveness, the easy words that came to you before—they’re all gone. You threw them out, remember? So you let your emotions take over and taint the thing with sentiment—an error on the part of every writer, but one that is more welcome than a misprint. The cycle repeats: You try to describe the thing anew, you throw it, you forget about it, it comes back to you.

So we have the method down to a tee—what, then, do we make of the reason? Many writers, including myself, develop methods and put lines to paper without much reason; we do it because we can and we want to, and the writer is someone who does not get paid enough to turn her pain into art—she does so of her own volition. The writer’s job is also to make the reader complicit in her crimes: If I can tie you to my sorrows, make you feel something, lead you to read the same sentence twice like it is your birthright, then I’m not in this alone. No weapons, only nibs. No coercion, only some foolish empathy. And to make you an accomplice, I need to give you reason.

So, I ask, am I playing fetch to keep the memory in my life like some kind of eulogy renewal? Or am I trying to dissect it until it is no longer the initial memory?—Gnaw at it to the point where it no longer carries its original form, then give it a different name. It’s how friendship becomes disappointment, how love becomes blind infatuation, how a goodbye at a train station becomes abandonment. I run after what I want the memory to be while my past runs after me; between the three of us, I am the slowest, so what-should-have-been moves out of sight as I lose my momentum and get tagged. And, what is it: The further away I move from a memory, do I gain or lose my sense of self? Should I weigh heavier what others know about me or what I know about myself? Which side comes with more bias? Which side comes with more truth? Which narrative will be the one to get my papers into heaven?

I don’t know the answers (all I know is to write), but maybe you do. And if you do, you know to find me in the depths of the metaphorical meadow, where I’m throwing sticks with a dog that no longer resembles a dog. And if you do, but you spare no desire to free me from my inked chains, I will find some way to forgive you.

playing victim

My oldest friend used to live thirty minutes away from me on a good day without traffic; now, she lives four hours away from me. We see each other once a year on average, and, without fail, a key agenda of our reunion is the regurgitation of my life story. Playing a decade worth of fetch on steroids, all in two hours. I talk about the un/fortunate circumstances that have befallen respective chapters of my life and justify why it is unfair, why I deserve different. Amelia does not exert bias just because she’s known me the longest—she tells it like it is every time. She asks if I have considered that I am the common denominator in a series of similar issues. She questions if my self-destructive tendencies originate from a need to control outcomes. I try to wrestle my way through with a series of ‘yes, but’s. She brings up an indisputable list of evidence and witnesses, shines the lamp in the interrogation room brighter into my eyes. The job of a best friend is to be a mirror, and Amelia does this exceedingly well.

So I look in my bathroom mirror at three in the afternoon and it takes everything in me to convince anyone who will listen that your new girl is better. Not better than me—please never commit such a blunder—simply better for you. My tongue turns rancid after surrendering my statement and I wonder if it’s because the truth had gone stale in my mouth or if my resentment had bittered. Can you tell the truth without resentment? Without longing for a version of the story that had been embellished in your favor?

I have since spring last lost the privilege to think about the fact that it ended. I still think about how it ended, and it’s important to differentiate the two. Because I’m not trying to find my way back to you (I grew up on an island and I know how to burn bridges). I’m trying to claw my way back to the memory that has been buried so deep that the canine of my subconscious cannot even sniff out its location. I ran too fast from the scene of the crime and forgot to investigate how it all ended. I ran because to stay would be to admit that I was part villain. I ran because to protect the young girl in me who only ever wanted to be fed love on a silver spoon, your name had to appear next to the villain’s name when the credits rolled. Otherwise, who would be willing to forge that spoon and pour out the love and peel open my mouth when the sequel comes around?

I am not a lover, I don’t need closure, but I am a writer, which means I need to get my story straight. Not the story, my story. And if you’d like to know where I learned to modify the narrative, I’ll give you this one truth: Instead of asking to be loved the way I want, I have always taken the love I’ve received and changed the narrative in my head to self-persuade that the form and volume of the love is enough. I’d rather burden myself with the intricacies of words and dance with the devil in the details than bother someone—than beg someone—to love me the right way. Nothing worse than a misprint than to lick the dog bowl for remnants of love. Again and again.

But I should have known better as a writer—and I know now—that in a story, the victim can also be—and almost always is also—the villain.

playing dead

In the middle of the meadow, where the grass grows tall and the sun barely meets the soil, the young girl who was never loved the way she wanted to be loved lies still. There is no headstone, for there are no mourners here. I have made a habit of poking her for some minor reaction, some pitiful moan, some desperate digging her nails into the soil to carve out the name of her assailant, but I’ve recently stopped. I’ve recently come to know peace.

The wind unleashes itself past the green and sends her hair fluttering. Her lips remain slightly parted as if some words never made it out; her fingers resume a writing stance, though there is no longer a pen for her to grip. There is only a faint, distant barking and the protrusion of blooms out of thawed earth.

All her life, she has only ever had three responses to her writing:

One, the kind that takes her letters for granted.

Two, the kind that keeps her letters a secret.

Three, the kind who, without prompting, will repeatedly tell others ‘she’s a writer’ like it’s a shinier occupation than a lover.

I think the last one finally laid her to rest. I think when she knew her words would be read and believed and framed and caressed by at least one from here on out, the need to play fetch or victim ceased.

The canine of my subconscious comes back with a thing in its mouth. I learn to let the earth yawn for burial and save my arm a swing.

Leave a comment